Dance Paradigms (Part 7: Postmodern Dance)

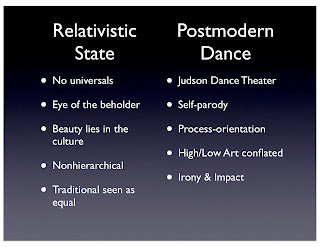

Following the Absolutistic and Multiplistic states, Graves called the next stage of development the Relativistic state. With the Relativistic state, we enter the world of contemporary postmodernism. Beauty is no longer absolute—it is, “created by culture and determined by human view” (Martin-Smith). No universals exist. It is personal to the extreme: whatever the artist says is beautiful is beautiful.

Following the Absolutistic and Multiplistic states, Graves called the next stage of development the Relativistic state. With the Relativistic state, we enter the world of contemporary postmodernism. Beauty is no longer absolute—it is, “created by culture and determined by human view” (Martin-Smith). No universals exist. It is personal to the extreme: whatever the artist says is beautiful is beautiful. Personally, when I tired of the achievement oriented modernist uptown dance scene in New York City, I started to explore different approaches in order to find a more personally relevant voice. And, as my body no longer had the elasticity and bravura strength of my youth, I explored ways of moving that were not simply about spectacular displays of skill. And in this exploration, I started to choreograph.

Unfortunately, my palette of movement options was greatly limited by my technical training. I was becoming postmodern in my thinking without an awareness of the postmodern movement in art and dance. As I began to discover the link between the two, I became more curious about the concepts and processes underlying postmodern dance. However, I had to clarify, for myself, what I think is a common dancer’s misunderstanding about postmodernism.

Unfortunately, my palette of movement options was greatly limited by my technical training. I was becoming postmodern in my thinking without an awareness of the postmodern movement in art and dance. As I began to discover the link between the two, I became more curious about the concepts and processes underlying postmodern dance. However, I had to clarify, for myself, what I think is a common dancer’s misunderstanding about postmodernism.Postmodern Confusion

Many young professional dancers and college undergraduate dance students consider the postmodern movement in dance to be something that occurred in the 1960’s—usually isolated around the Judson Dance Theater years from 1962-1964. They define postmodernism tightly around the experiments of that period which worked to prove that anyone could be a dancer (no technique or training required), anything can be a stage, and anything can be a dance movement (walking, tying a shoe, eating cereal).

So what are the concepts? Since beauty is not cross culturally inherent and no universal of what is aesthetically beautiful can be defined, beauty is whatever the artist says it is. In dance, tying a shoe or masturbating on stage (seriously, a student and her mother checking out a college attended an MFA concert where this took place) becomes as legitimate a statement as the classicist’s display of beautiful line or the modernist’s expression of inner feeling in a deep contraction. In art, a crucifix immersed in urine joins the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel and Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d'Avignon as great works of art. While these examples sound shocking, they are important to understanding postmodernism.

Self-parody became a new mark of the choreographer. The modernist’s primitivism was abandoned and equal respect was given to traditional forms of dance. In the postmodern era, we see respect for tribal and ethnic dance forms as equal to all others. The concepts of high and low art and those of fine and commercial art become conflated—think Warhol’s soup cans.

Contemporary Dance

As I mentioned earlier, some dancers in the early 21st century do not recognize they are part of the postmodern era. They define contemporary dance as a fusion of techniques. To them, contemporary ballet is often a fusion of ballet and modern. Contemporary jazz is a fusion of jazz and modern.

This concept of fusion is indeed a postmodern trait, especially with the conflation of commercial and fine art. However, this conflation has muddied the waters between the avant-garde and popularism. Popularism has led to a version of contemporary dance that is a simple fusion of “whatever the audience/choreographer likes best”. Today, audience members watching this fusion version of ‘contemporary dance’ on television shows like “So You Think You Can Dance” are shocked when they attend a contemporary dance concert because the two look nothing alike.

Contemporary dance today, as I see it, is a further development of postmodernism (perhaps transmodernism) that integrates, rather than fuses, postmodern processes with modernist techniques as well as classical and traditional elements.

The difference between contemporary dance and ‘contemporary dance ala reality television’ is that the former develops off of the strengths and weaknesses of the preceding and the latter just capitulates to popularist desires. One is an extension of postmodernism and is growing with the thought, philosophy, and artistic developments of our age, the other is responding directly to commercial and entertainment trends of our age.

This begs the questions, what lies beyond the postmodern paradigm in dance?

Comments

Post a Comment