Dance Paradigms (Part 6: Modern Dance)

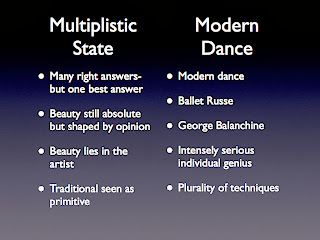

The transition for Graves from the Absolutistic to the Multiplistic existence surfaces in a change from “a submissive state to one of selfish independence”. The shift from Medeival Times into The Enlightenment is the large-scale rendition of this transition. It is Multiplistic because now there are a plurality of right answers—not just one. In the case of the dancer, she begins to question the dogma she has been reared on in order to find the way, perhaps the style, that works for her personally.

My final year of college I started to doubt my discipline. I mean, I embraced how it helped me become a much stronger technician than I was when I began, but I no longer idolized classical ballet or Graham technique. I wanted, at that time and for years after, to find the technique or techniques that best helped me improve.

For me, that came when I was introduced to Horton technique from a guest artist workshop with Milton Myers. Conservatory programs often straddle the line between Absolutist and Multiplistic thinking. Ironically, New York City Ballet has become classically absolutist in its attempts to preserve the Balanchine repertory while Balanchine himself took a very modernist approach to a classical form.

In modernism, whether we are speaking of dance, art, or philosophy, beauty and value are shaped by human view. Yes, beauty is still absolute, but it is open to opinion. What is most beautiful to one culture may not be the most beautiful to another.

This begins to sound more like what we are used to in the first decade of the 21st century. We generally think pluralistically and we owe that to modernism. Modernism freed us from the oppressive hierarchy of absolutism (often in the guise of classically dogmatic religion). However, there is a catch.

Modernism believes there is more than one right way, but that one way, in particular, is better than others. There are many paths to the top of the mountain, but one is quicker or safer or more beautiful than the rest.

With modernism and the world of 20th century American concert dance, we see the growth of a multitude of approaches and techniques: Graham, St. Denis, Humphrey-Weidman, Limón, Taylor, Horton, etc. They each offered their personally subjective version of the beautiful and accepted the variety of other approaches, albeit often with scorn and derision. To them, beauty was real and existed inside the artist, yet they were competing to see which one had the best grasp of beauty.

It is interesting to see how the modern perspective treated traditional dance forms. From the modernist perspective of personal authority, traditional dance forms were seen as primitive, but not without beauty.

Modernists found beauty in traditional forms that the classicists scoffed at; however, the modernists still felt that their own artistic conceptions were superior to the traditional forms. This resulted in a trend of using ‘primitive’ material but recasting it in the modernists mold. From Pablo Picasso to Ruth St. Denis, primitivism in modernism (too many isms?) was the artistic counterpart to colonialization. The modernist interest in traditional forms was well intended, but their inability to escape from their modernist perspective led to exploitation.

Modernism introduced Multiplistic thinking and subjectivity that led to a plurality of competing modern dance techniques. These techniques and their progenitors took themselves almost as seriously as the Absolutist authorities they supplanted. They replaced the one objective hierarchy with a plurality of hierarchies.

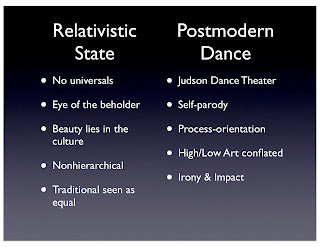

Postmodernism would take modernism a step further and, in doing so, pull the rug out from the concept of hierarchy altogether.

Comments

Post a Comment