Dance Paradigms (Part 5: Classical Dance)

When the Egoistic dancer looks for greater meaning and the traditional and popular forms of dance (Tribal, Folk, Social, Ehtnic) are codified into a canon, the classical forms emerge—like Bharatanatyam (one of eight forms of Indian classical dance) or classical ballet. In the western world, ethnic court dancing transitioned into classical ballet with the canonization that came from Pierre Beauchamp and Jean-Georges Noverre. For the purpose of this series of posts, which follow the development of western concert dance, I will focus on ballet as the exemplar of the classical credo.

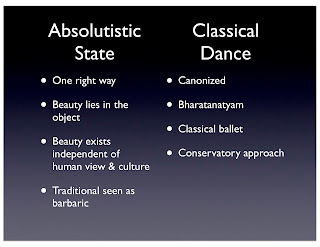

Classicism fits in with the Gravesian framework in the

Absolutistic state of thinking. Graves wrote, “Thinking at this level is

absolutistic: one right way and only one right way to think about anything”.

From a classical/absolutistic perspective, there is one superior form of dance.

All other forms are barbaric or the work of savages who are not sophisticated

enough to appreciate the objective beauty. The fact of this beauty exists

independent of human view and culture.

One cannot, from a classical/absolutistic viewpoint, simply

claim that one prefers a traditional tribal dance form over that of classical

dance without submitting oneself to the accusation that one has no taste. For

the classically minded, beauty lies in a set of universals which must not be

questioned. For classical ballet, those universals include the concepts of

line, symmetry, and harmony.

The various classical ballet traditions of Cecchetti,

Vaganova, Bournonville, and French developed around the same concept of 'the

beautiful' in dance. The differences in their approaches are minimal as they

all strove toward the same ideal of perfection.

For me personally, I entered college from an initial

Egoistic state of confidence and the desire to express myself. My first year

was an eye-opening struggle as I was forced to submit to the discipline and

structure of the ballet program.

During my second and third years I dedicated myself as a loyal disciple to the Cecchetti and Vaganova ballet classes and the Graham

modern classes. At that time, I accepted that these were the pinnacle forms of

artistic dance. Conservatory programs, especially those focused solely on classical ballet, are often strongly absolutist in thinking.

Classical dance demands a dogmatic dedication and defies innovation or change. Classical thinking has a fundamentalist foundation. Other ways and forms are not simply lesser ways, they are wrong. However, one can be a classicist in approaching a non-classical form.

For instance, today there are followers who believe with righteous fervor about the superiority of Martha Graham’s modern dance, George

Balanchine’s neo-classical (modernist) ballet, or Steve Paxton’s Contact

Improvisation. One can be a classicist about a modern form (Graham technique)

or a classicist about a postmodern form (Contact Improv).

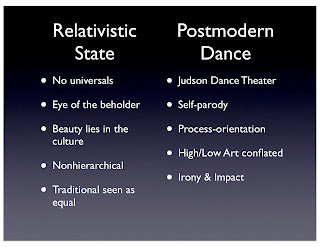

If, as Graves said, an “era builds on the strengths and weaknesses of that preceding it,” then the absolutism of classical dance paved

the way for the modern era that challenged the dogma of one right way that

exists outside of the individual, to find many subjective alternatives

(Martin-Smith). See Modern Dance.

Graves, Clare W. The Neverending Quest. California: ECLET, 2005.

Martin-Smith, Keith. “On the Future of Art and Art Criticism.” Integral World. N.p. N.d. Web. November 6, 2009.

Thanks for expressing ideas about the dance. Dance give the life to the living style.

ReplyDeleteClassical Dance Classes in Bangalore| Bharatnatyam Classes in Koramangala| Learn Mohiniyattam In Bangalore| Bharatnatyam Classes in Bangalore| Bharatnatyam Classes in Whitefield| Bharatnatyam dance class near me| Top Bharatnatyam Classes In Kormanagala| Bharatnatyam Classes In BTM| Bharatanatyam Dance Classes Bangalore